Your brain physically won't allow you to become a future version of you that it hasn't experienced yet… Your future self is not imagined into existence. It is trained into existence.

The idea is that the brain, being a "predictive engine" molded by past experiences, resists any future identity for which it has no evidence, and that only through repeated attention and action can one "train" the brain to accept a new self. How does this hold up under scientific scrutiny? Below, we examine what neuroscience and cognitive psychology say about how our brains form identity, why change is hard, and how new habits or "future selves" can actually be developed.

The Brain as a Predictive Engine Built on Past Experiences

Neuroscience increasingly supports the view that the brain is not a passive reactor but a prediction machine. Our perceptions, thoughts, and choices at any moment are guided by the brain's best guesses based on what it has learned in the past. In other words, the brain constantly asks (unconsciously), "When I've been in a similar situation before, what happened and what did I do?" and uses that memory to interpret what's happening and plan the next move. This predictive processing means that past experience heavily constrains what the brain perceives as "normal" or possible.

As cognitive scientist Andy Clark, Professor of Cognitive Philosophy at the University of Sussex and author of The Experience Machine: How Our Minds Predict and Shape Reality, explains, the brain draws on a lifetime of past experiences to reconstruct fragments of prior encounters and use those internal models to interpret novel input and decide how to respond. According to this view, what we experience as reality isn't a neutral mirror of the world but the brain's "best guess" shaped by what it has learned previously—a continually updated predictive model that privileges familiar patterns and expectations.

Countless connections among nerve cells in our brain are recalibrated to accommodate new experiences. It's as if we reassemble ourselves daily… and the glue that holds together our core identity is memory.

Importantly, this predictive nature extends to our self-concept. The brain builds your sense of identity and capabilities largely from accumulated memories of your actions, emotions, and attention patterns over time. As we go through life, "countless connections among nerve cells in our brain are recalibrated to accommodate [new] experiences. It's as if we reassemble ourselves daily… and the glue that holds together our core identity is memory." In short, who you believe you are (and what you believe you can do) is grounded in the evidence your brain has collected from your past experiences. If all your life you've received feedback that you're, say, shy or bad at math, your brain's model of "self" will reflect that history and predict that that is who you are likely to be going forward.

Neuroplasticity: How Repeated Experiences Wire Your Identity

The flip side of being constrained by past experience is that the brain is plastic—it physically rewires itself with new experiences. Neuroscientists have demolished the old idea of a fixed adult brain: "Your brain is not concrete; it's a dynamic, moldable organ that can reorganize itself by forming new neural connections throughout life."

Every action you repeat, every emotion you dwell on, every skill you practice causes certain neural circuits to strengthen (through repeated use) while unused connections weaken or prune away. This process is sometimes called experience-dependent neuroplasticity—the brain's wiring adapts to what you do and pay attention to, for good or ill.

Learning a new skill physically creates and strengthens new neural pathways. The more you practice, the more efficient the highway becomes.

As Donald Hebb, PhD, a foundational neuropsychologist and pioneer of neuroplasticity, demonstrated, repeated patterns of thought and behavior physically strengthen the neural circuits that support them—a principle now known as Hebbian learning. Building on this work, psychiatrist and researcher Norman Doidge, MD, has shown that learning a new skill or repeatedly choosing a new behavior reinforces specific neural pathways, making them faster and more efficient over time, while neglected pathways weaken and are eventually pruned. In this way, habits are not merely psychological preferences; they are biological processes. What we repeatedly do reshapes the structure of the brain itself, gradually shaping our identity, capabilities, and sense of self.

This has two big implications. First, if your current identity is built from past habits and experiences, it is indeed difficult to abruptly imagine yourself into a very different identity without any bridge of experience. There are real neural networks in place coding for "who I am" based on years of reinforcement, and those don't instantly disappear. Second, the encouraging news: those neural networks can be modified or expanded. New actions and thought patterns, repeated often enough, will leave physical traces in your brain. Change is possible, but it typically requires training new patterns into the neural circuitry, not just one-off epiphanies.

Familiarity Over Uncertainty: Why Change Feels Hard for the Brain

Why would the brain "resist" a future for which it has no evidence? From an evolutionary perspective, our brains are wired for survival first, which means minimizing surprises and errors. A novel, untested identity or lifestyle is, to the primitive brain, an unknown—and unknown can equal unsafe. Thus, we have a bias toward the familiar.

The brain is fundamentally biased toward safety and predictability—familiar patterns are neurologically preferred because they generate fewer surprises and lower metabolic cost.

As Joseph LeDoux, PhD, Professor of Neural Science at New York University and a leading researcher on the brain's threat and survival systems, has shown, the brain is fundamentally biased toward safety and predictability. Building on this, Karl Friston, MD, PhD, whose work on predictive processing and the Free Energy Principle explains how the brain minimizes uncertainty, demonstrates that familiar patterns are neurologically preferred because they generate fewer surprises and lower metabolic cost. As a result, the brain often selects known comforts—even unhealthy ones—over unfamiliar alternatives, because the familiar has already proven survivable. This bias toward the known is the neurological basis of what we commonly call the "comfort zone."

Physiologically, stepping outside your comfort zone really does register as a challenge. New experiences require more mental resources—studies indicate the brain uses ~20% more energy to process novel situations compared to routine ones. That's why trying to change can feel draining or uncomfortable at first—your brain is literally working harder, and an alarm system in the emotional centers may be waving a caution flag.

The amygdala (the brain's threat detector) often kicks in when you do something unfamiliar, triggering anxiety or stress responses (racing heart, hesitation) as if to say "careful—this is new!" Importantly, neuroscientists emphasize that this initial resistance or discomfort "isn't a sign something's wrong. It's just your brain doing exactly what it's designed to do" in protecting you. Recognizing this built-in bias helps explain why we so often avoid or abandon big changes: the brain's default is to conserve energy and stick to known-safe routines unless we repeatedly show it that a new path is safe and rewarding.

When the Future Self Feels Like a Stranger (Self-Continuity)

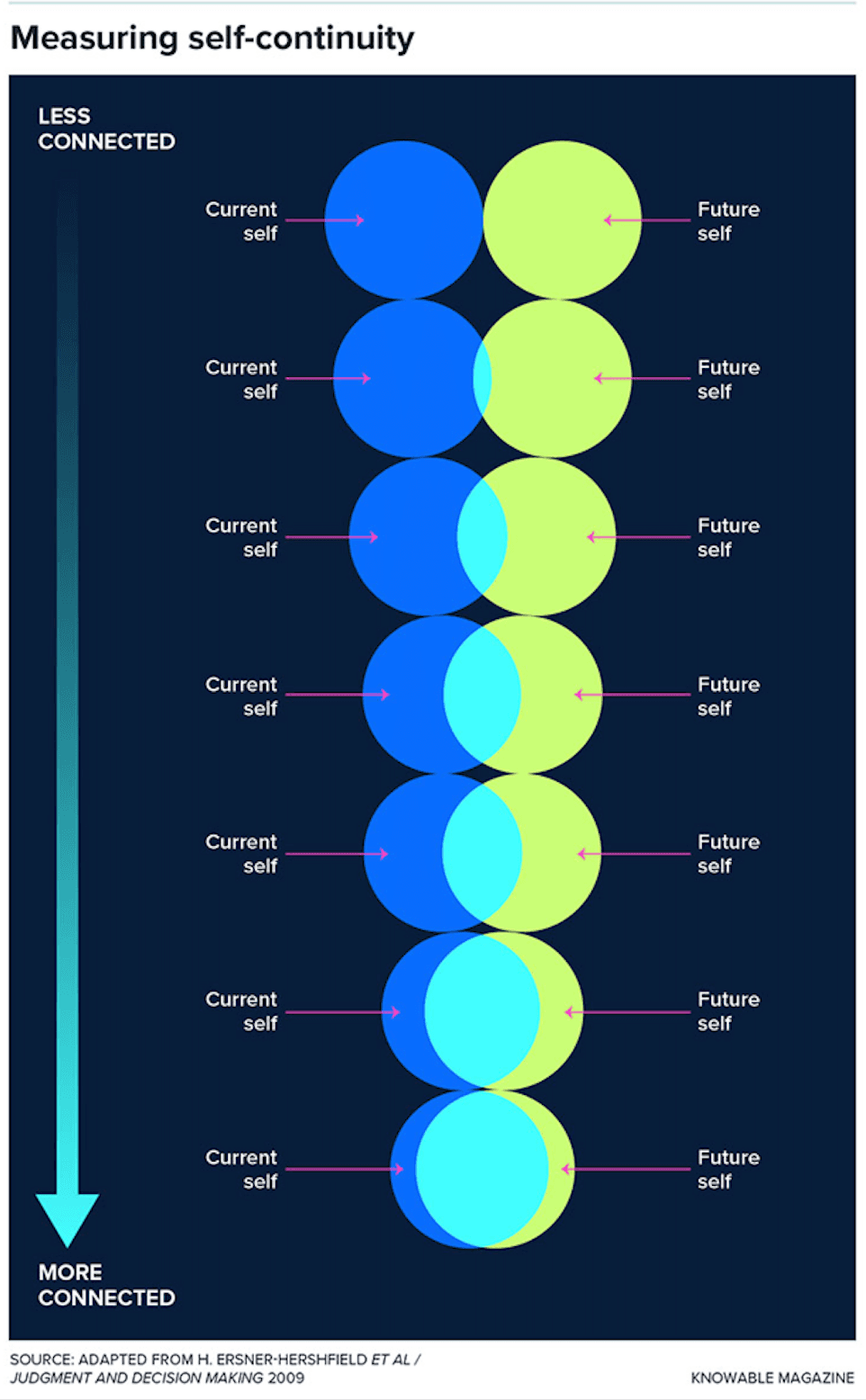

One consequence of the brain's reliance on past experience is that an imagined future self with no precedent can feel not truly "real" or self-related. Psychologists refer to this as future self-continuity—the degree to which a person feels psychologically connected to their future self. As Hal Hershfield, PhD, Professor of Marketing and Behavioral Decision Making at UCLA and a leading researcher on future self-continuity, explains, "Some people don't even think about that future self, and it feels almost like a stranger." Experimental studies consistently show that many people experience surprisingly low continuity with their future identity, treating their future self as psychologically distant rather than as an extension of who they are now.

If your brain effectively treats "Future You" as someone else, it's hard to marshal motivation and resources for that unknown person. Indeed, researchers have found that people who feel little connection to their future self are less likely to make choices that benefit that future self (for example, they may fail to save money, forego healthy habits, or avoid pursuing long-term goals)—essentially defaulting to immediate comforts instead. In contrast, those who vividly identify with their future self (high overlap between now/future) show more drive to invest in long-term outcomes.

Neuroscience studies support this idea: brain imaging shows that thinking about one's distant future self can activate patterns more similar to thinking about a stranger than about one's present self, especially in people with low self-continuity. In simple terms, futures that lack experiential evidence feel "biologically unreal" to the predictive brain. The brain hasn't seen you as a successful author, fit and energetic, or living in a new country, so it may flag those prospects as unlikely or even threatening.

This can manifest as subtle self-sabotage—procrastinating on steps toward the goal, diverting attention when the topic comes up (attentional avoidance), or quickly reverting to old habits after a burst of motivation. It's not a mystical force blocking your "manifestation," but your brain's natural skepticism and risk-aversion toward what it hasn't yet verified.

Attention: The Gatekeeper of Change and Learning

How, then, does one get the brain to accept and embrace a new identity or skill? A core principle in cognitive neuroscience is that nothing changes in the brain without attention. In fact, researchers often call attention the "gatekeeper" of neuroplasticity and learning. We are bombarded by stimuli and potential behaviors, but the brain will only seriously encode and adapt to those things we consistently focus on.

Neural change is gated by attention—plasticity occurs most powerfully when attention is directed, engaged, and sustained.

If an experience isn't attended to, it's unlikely to produce lasting neural change—essentially, "brains don't change without sustained attention." This is why simply wishing for a different future or casually visualizing it a few times may have little effect on actual identity; such thoughts are fleeting and often not deeply encoded as "self-relevant." On the other hand, repeatedly directing your attention to a new pattern (a goal, a role model, a set of behaviors) tells your brain "this matters—make this part of what defines me."

Over time, what you pay attention to and practice most becomes what your brain perceives as normal for you. As Michael Merzenich, PhD, Professor Emeritus of Neuroscience at the University of California, San Francisco and one of the world's leading researchers on neuroplasticity, has shown, neural change is gated by attention—plasticity occurs most powerfully when attention is directed, engaged, and sustained. In this view, attention determines which neural pathways are strengthened and which remain unchanged, making it a primary mechanism through which identity and capability are reshaped.

This gatekeeping role of attention is evident in many domains. For example, in skill learning, a person who intently focuses on improving (say, listening closely to musical notes to train their ear) will physically rewire auditory circuits, whereas someone passively hearing the same sounds with no attentive effort shows little change. Regarding identity, if you start to identify with a certain trait ("I am a leader," "I am a healthy person") and consistently attend to evidence of that trait in your behavior, your brain will increasingly tag that trait as self-related and strengthen the neural links accordingly. In short, attention literally selects what gets "written into" your brain's model of who you are. It is the first step in any real change—you must shine your mental spotlight on the new self you aim to build.

Action and Feedback: Training the Brain with Small Steps

While attention opens the door, experience must walk through it. True identity shifts are achieved not just by thinking differently, but by acting differently, repeatedly, so that the brain gets new feedback. Neuroscience shows that attempts to make big drastic changes in one leap often trigger strong resistance and fade-out, whereas "tiny, consistent actions" are far more effective at reshaping the brain's wiring.

Each small successful action is a proof point: evidence to the predictive brain that "hey, we survived this and even got rewarded." Over time, these small wins accumulate into a new normal. In fact, research indicates that gradual incremental changes can reconfigure neural structure "more effectively than big, dramatic changes." This is because frequent repetition with positive feedback leads to stronger synaptic reinforcement (the brain says "this is working, let's make this circuit more efficient"). In practical terms, if you want to become that "future you," you literally train for it in little everyday ways.

Those first steps toward personal growth might feel wobbly—you're literally carving new neural pathways.

Consider what happens in the brain when you adopt a slightly unfamiliar action and stick with it. At first, it feels awkward—you're forging a new neural pathway where none existed. "Those first steps toward personal growth might feel wobbly—you're literally carving new neural pathways." But each repetition of the behavior lays down more myelin on the neurons (like paving a road). The pathway gets faster and smoother; the action starts feeling more natural.

Importantly, feedback solidifies the change. Each small accomplishment triggers a dopamine release—a neurochemical reward that makes you feel good and motivates you to do it again. That could be external success (e.g. finishing a short workout and feeling proud) or even just an internal "good job" acknowledgement. This reward feedback tells the brain to prioritize and remember this activity. In essence, you create a self-reinforcing loop of attention → action → reward, which gradually shifts your identity and comfort zone boundaries.

The Attention-Action-Feedback Loop

Neuroscientists and psychologists often describe the process of personal change as a continuous loop or cycle. Breaking it down:

1. Attention and Intention

You focus on a desired change or future self, directing your awareness to what you want to become (e.g. routinely picturing or thinking about the behaviors of a fit person or a successful writer). This sets the stage by priming the brain to treat those behaviors as important.

2. Action (Experience)

You take small, manageable steps that embody that future identity—slightly outside your usual comfort zone but not so far as to overwhelm. For example, if your goal identity is "a confident public speaker," your action might be volunteering a short comment in a meeting. The key is repetition: doing it again and again so the experience isn't a one-off.

3. Feedback and Reward

You observe the outcome and feel the effects. Maybe the meeting comment earns a nod of approval (external feedback) or you simply feel a rush of pride for being brave (internal feedback). The brain registers this as a reward. Positive feedback releases dopamine, which strengthens the new neural pathways and reinforces your motivation to continue. Even if the outcome isn't perfect, surviving it without disaster is itself feedback that "this new behavior didn't kill us"—valuable evidence for the brain.

4. Adaptation (Updating the Model)

With attention and repeated rewarding practice, your brain updates its internal model of "who I am." The unfamiliar action starts to feel less foreign; you might start thinking "maybe I am the kind of person who can do this." Neurally, the circuits supporting the new behavior become more efficient and ingrained, while old habit circuits associated with the former self may weaken from disuse. Over time, the small changes accumulate and your identity shifts almost organically—because you've earned that evidence within your nervous system.

Through this loop, your future self is essentially trained into existence. It's not magic or wishful thinking; it's a gradual biological and psychological transformation.

Through this loop, your future self is essentially trained into existence. It's not magic or wishful thinking; it's a gradual biological and psychological transformation. Each cycle of the loop expands the range of what your brain considers "normal for me," allowing you to venture further next time. For example, today you run for 15 minutes as a "slightly unfamiliar action"; a week later, 15 minutes is easy (now familiar) and you can push to 30, and so on. The brain's prior limitations are continuously being pushed outward by experience. In the words of the claim: the future self isn't just imagined, it's built brick by brick via this attention-action-feedback cycle.

Conclusion: From Vision to Reality, Backed by Science

In light of the evidence, the claim captures a fundamental truth: our brains do not easily permit us to become something radically new without putting in the work to retrain them. It's not that change is physically impossible—but it is inherently at odds with how the brain optimally operates. The brain relies on past evidence and resists what it hasn't encountered; therefore, to achieve a "future you" that diverges from your past, you must provide your brain with new evidence, repeatedly. This is entirely consistent with established science: the brain is predictive and experience-dependent, it craves familiarity for safety, and it only rewires through focused attention and repeated practice.

Notably, research suggests that belief and visualization can play an important role in initiating identity change by orienting attention and motivation toward a new possible self. Mental rehearsal can prime relevant neural circuits and make new behaviors feel more accessible. However, without repeated real-world action and feedback, these changes remain fragile. The brain's deeper identity systems—automatic habits, emotional predictions, and self-concept—update primarily through embodied experience. Lasting identity shifts are therefore not sustained by belief alone, but by lived evidence that trains the brain to recognize a new version of the self as real and survivable.

As we've seen, imagining a future self in abstraction often feels hollow unless it is paired with small, concrete behaviors that mirror that future in the present. When people engage with their future selves through repeated attention and immediately follow that attention with tangible, low-risk actions, the brain begins to register continuity rather than distance. These small, embodied signals provide experiential evidence that helps the nervous system update its internal model of who you are becoming. In this way, even modest present-day actions allow the brain to "sample" the future, making it feel real, survivable, and worthy of further investment.

Once you realize your brain builds reality, you gain the power to change it.

In summary, the claim that "Your future self is not imagined into existence. It is trained into existence" is strongly affirmed by current neuroscience and psychology. The brain can indeed "refuse" futures that lack evidence by undercutting your motivation or focus, but this is a protective mechanism we can work with. By consciously looping through attention, action, and feedback, you provide the needed evidence and gradually earn your way into that future state. Or as Lisa Feldman Barrett, PhD, neuroscientist and author of How Emotions Are Made, has argued, once you understand that the brain actively constructs reality from past experience and prediction, you gain the ability to change that construction by changing the inputs it learns from.

In practical terms, you become your future self by consistently doing, feeling, and living small pieces of that future self, until your brain updates its definition of who you are. This is not just motivational rhetoric—it's grounded in how neural plasticity and predictive processing shape our identity over time. The path to personal transformation, therefore, is less about wishing and more about training: mindfully guiding your brain, step by step, to allow the "you" that you aspire to be.