What looks like a personal 'trait' may actually be a state—an oscillation in response to the environment, as the body constantly balances between opposing needs.

Polarity in human behavior isn't just a quirky idea from personality tests – it reflects a deeper biological law. Our bodies and brains are built on dynamic opposites working together. Understanding polarity as a fundamental principle of biology (rather than a fixed trait model) can change how we view stress, performance, and even leadership.

This perspective shows that what looks like a personal "trait" may actually be a state – an oscillation in response to the environment, as the body constantly balances between opposing needs. Below, we explore how polarity functions as a homeostatic mechanism in our nervous system, why extreme behaviors often signal stress (not character), how our talents and "weaknesses" boil down to energy trade-offs, and why true balance in healthy systems is dynamic – more like a pendulum swinging than a scale frozen in place.

Polarity and Homeostasis in the Nervous System

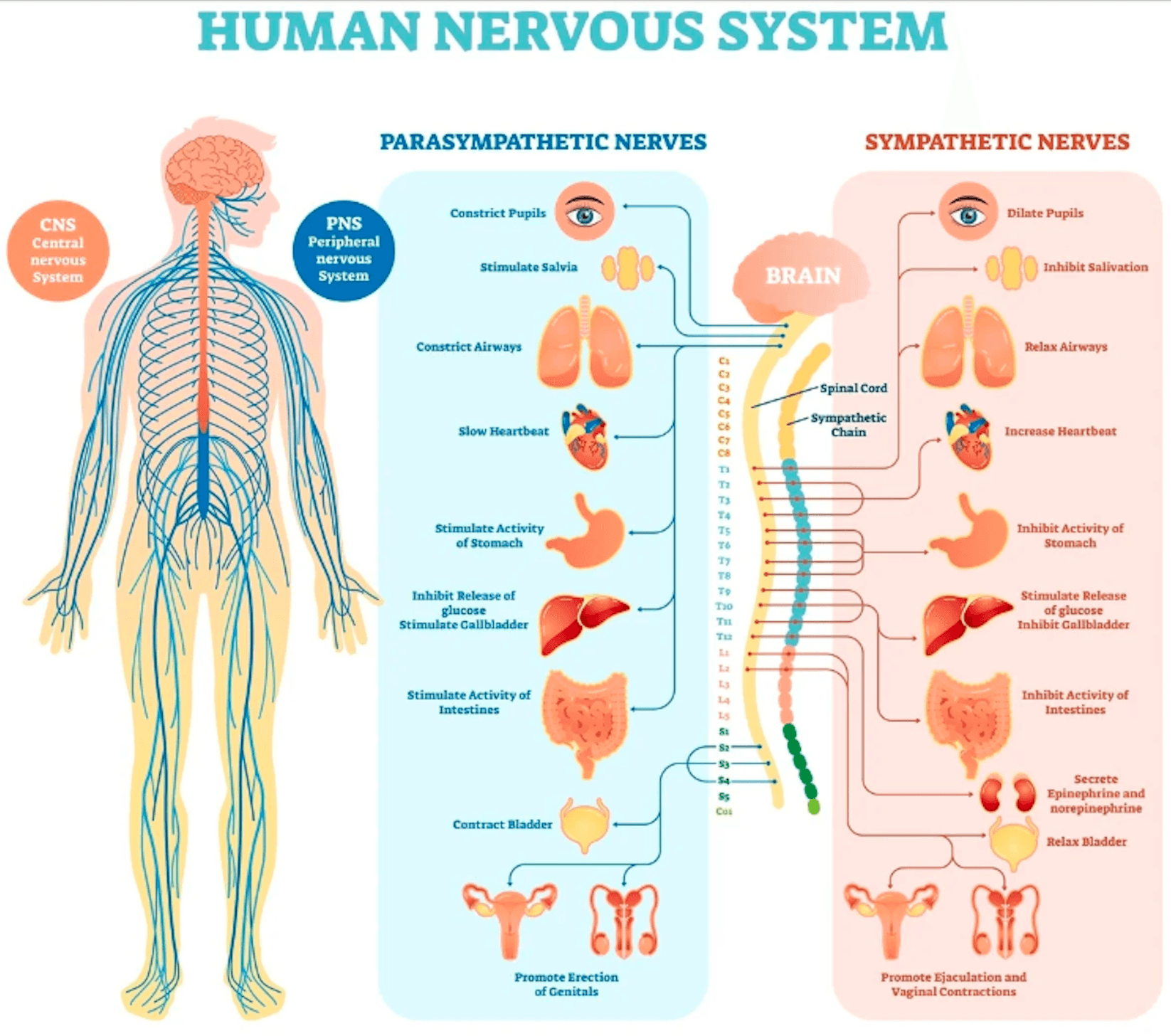

The human autonomic nervous system is divided into two complementary branches – the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems – which have opposing effects on organs to maintain internal balance. The sympathetic branch triggers "fight-or-flight" responses (speeding heart rate, raising blood pressure, inhibiting digestion), while the parasympathetic branch does the opposite – promoting "rest-and-digest" functions (slowing the heart, stimulating digestion and recovery).

These two systems act like a seesaw: when one is active, the other calms down. This balancing act between sympathetic and parasympathetic is key to our body's well-being and survival. In effect, the nervous system maintains homeostasis (internal stability) through polarity – it constantly toggles between high-alert and calm states to keep vital conditions in a healthy range.

Polarity is built into our physiology as a law of balance through movement – a yin-and-yang of biology that keeps us alive and responsive.

For example, if a threat appears, the sympathetic system kicks in to mobilize energy; once the danger passes, the parasympathetic system takes over to bring you back to baseline. This dynamic polarity is a fundamental biological mechanism – it ensures we can respond to challenges and then recover rather than getting stuck in one extreme state.

Notably, this idea of balancing through opposites isn't limited to the nervous system. Throughout biology, stability is often achieved via oscillation between two poles. Physiologists distinguish homeostasis (holding variables steady) from allostasis – "maintaining stability through change." While homeostatic control reduces variability, allostatic processes embrace variability as a way to adapt to changing conditions.

In other words, healthy living systems don't find a single static equilibrium and sit there; they maintain balance by continuously adjusting – like a thermostat that constantly turns heating or cooling on and off to hold a temperature. Our autonomic nerves, hormones, and even cellular processes work in opposing pairs to fine-tune our internal state.

When "Over-Indexing" Is a Stress Response, Not a Trait

We often describe people by their dominant traits – like being "too analytical" or "too impulsive." But extreme, one-sided behavior (what some call over-indexing on a trait) may actually be a sign of the nervous system under stress, rather than an ingrained personality feature.

For instance, imagine a leader who micromanages every detail and can't let go of control. Is that simply her personality? Or could it be her nervous system's polarized stress response – stuck in high gear, perceiving threat in any uncertainty? Research on chronic stress suggests that what seems like someone's personality can in fact be their survival instincts taking over.

Under prolonged pressure, our brains adapt by leaning hard into certain behaviors that helped us cope in the past. We might become hyper-vigilant, always anticipating problems, or conversely shut down and withdraw.

Over time, these responses can start to feel "wired in" as if they're just who we are. Psychologists note that chronic stress essentially trains the nervous system to stay on high alert, reshaping our default behaviors. Someone who over-indexes on a behavior – say, always pushing for productivity and never resting – is often mirroring the classic fight-or-flight activation of the sympathetic nervous system. Their body acts as if it's under threat 24/7, which can look like a "driven" or anxious personality.

On the flip side, a person who seems consistently detached or unmotivated might be stuck in a protective freeze or burnout state – the other side of the polarity – which can be mistaken for laziness or apathy. The key insight is that extreme behavioral patterns are usually the nervous system's way of adapting to stress, not an immutable trait.

Just as a thermostat stuck on full heat or full cold isn't functioning normally, a person "stuck" in one mode is often struggling with an internal imbalance. Recognizing this can foster empathy: instead of labeling someone as inherently rigid, scattered, or passive, we can ask what stressors or fears might be driving that polarized behavior, and how to help them feel safe enough to regain flexibility.

Behavioral Trade-Offs and Energy Allocation

Every behavior we exhibit comes with an energy cost. Our brains and bodies have a limited budget of energy, and they're constantly making trade-offs in how that energy is used. Think of it this way: if you shine a spotlight on one area, by necessity you leave other areas in relative darkness.

In life, when we focus our effort intensely in one direction, we often have less bandwidth for the opposite approach. These behavioral trade-offs are not moral failings; they are physics and biology. Just as an animal might trade off between spending energy on growth versus reproduction, or immunity versus activity, a professional might trade off between deep analytical work and social engagement in a given day – excelling at one while the other suffers.

Neuroscience research supports the idea that effort is inherently aversive to the brain – not because we're lazy in character, but because effort literally 'uses up' limited cognitive resources.

One study even found that people will choose physical pain over doing very difficult mental tasks, illustrating how strongly our brains avoid expending high cognitive effort. Why would evolution wire us to avoid effort? The answer lies in energy economics: the brain is only ~2% of our body weight, yet it can burn through about 20% of our daily calories – an energy hog by any measure.

Our bodies have therefore evolved caution in how we invest mental energy. Psychologists describe a cost–benefit analysis happening subconsciously – if a task is perceived as not worth the effort, we feel an urge to disengage or procrastinate. This isn't laziness; it's the brain's way of optimizing energy allocation. In practical terms, it means many so-called "bad habits" (like avoiding complex problems until deadline or sticking to familiar routines) are actually attempts to conserve energy for what seems most pressing or rewarding.

Understanding behavior as an energy allocation problem reframes the notion of "strengths" and "weaknesses." Often, what we call a weakness is simply the flipside of where our energy-driven strengths lie. For example, a person who is a brilliant creative thinker (pouring energy into imagination and big-picture ideas) might appear disorganized with details or routine tasks – not due to a character flaw, but because meticulous detail-work doesn't engage their brain's reward circuits enough to justify the high effort.

Another person might always be on time and orderly, but that leaves them little mental slack for spontaneity or creative risk-taking. Rather than viewing these differences as fixed traits, we can see a dynamic polarity at work: focusing energy in one domain inevitably means less energy in its opposite domain at that moment.

We Don't Lack Skills – We Protect Our Energy

Consider how we often say someone "lacks" a certain skill or quality. Perhaps an employee is labeled as lacking initiative, or an executive is seen as lacking empathy. In reality, humans are born with astonishing capacity to develop a wide range of skills – but we specialize in what we practice, and what we practice is guided largely by what our environment has demanded and by what our biology finds efficient to do.

Avoiding unnecessary effort is a deeply ingrained survival strategy. In our evolutionary history, wasting energy on tasks that didn't directly aid survival could be dangerous.

Often, when a person doesn't exercise a skill, it's because at some level they are conserving energy (or avoiding emotional risk, which in the brain feels like conserving energy/protecting safety). Anthropologists note that for most of human history, conserving energy whenever possible was crucial; "motion without purpose would be a waste" in the harsh calculus of survival. We have inherited brains that instinctively steer us away from expending effort on things perceived as low-value or high-risk.

This doesn't mean people never change or grow; it means that if a person consistently "opts out" of certain behaviors (public speaking, for example, or meticulous planning), it's worth asking why that expenditure of energy feels unwise to their system. Often, what looks like a lack of ability is actually an efficient protective mechanism.

For instance, a team member who doesn't voice opinions in meetings might not truly lack ideas or confidence – they may be conserving emotional energy (and avoiding the stress of conflict). A manager who "doesn't delegate" might not lack trust in others inherently, but perhaps their stress response tells them it's safer (or less energy-intensive) to just do things themselves.

Our bodies and brains are risk-calculation machines, honed by evolution to avoid unnecessary strain. Laziness, in a sense, is a natural baseline – a kind of energy-thriftiness found across many animal species that keeps us alive when resources are limited.

What does this mean for personal development? It's liberating: people are not fixedly "bad" at something – they have either not had sufficient need to develop that skill (their system didn't deem it worth the energy), or they face internal friction (fear, stress, uncertainty) that makes that activity energetically expensive. With the right motivation or a safer context, the calculus can change.

The Myth of "Balance" vs. the Reality of Oscillation

Finally, let's tackle the popular idea of balance. In self-improvement and leadership literature, we often strive for "balance" – work-life balance, balanced decision-making, a balanced personality. This conjures an image of a stable scale, everything perfectly even and steady. But biology teaches us that real balance is not a static midpoint – it's a dynamic oscillation.

A healthy system moves around an equilibrium; it doesn't sit perfectly still at equilibrium. In fact, if your internal state stopped oscillating entirely, you'd be in trouble.

A clear example is heart rate variability (HRV) – the slight fluctuations in time between your heartbeats. You might think a "steady" heartbeat is ideal, but actually, higher variability between beats is a sign of better health and adaptability. Why? Because HRV reflects the push-and-pull of your sympathetic vs. parasympathetic nervous system in real time.

When you inhale, your heart rate speeds up; when you exhale, it slows down – a subtle oscillation. High HRV means your heart can adjust on the fly, indicating your body is flexibly balancing between stress and relaxation inputs. People with higher HRV tend to handle stress better and recover faster, whereas low HRV (a very steady, unchanging beat interval) often signals a body stuck in fight-or-flight mode or exhausted state.

In other words, variability is healthy – it means you can oscillate appropriately between the poles of activity and rest. A total lack of movement (biological or metaphorical) is stagnation.

This principle applies broadly. Physiological balance is an active, ongoing process of correction, not a one-and-done achievement. Our body temperature, for example, isn't exactly 98.6°F all day – it hovers up and down in a narrow range, oscillating as we sweat or shiver to adjust. Likewise, emotional balance doesn't mean feeling calm all the time; it means having natural periods of excitement and agitation that are counterbalanced by periods of calm and reflection.

Even in organizations or personal life, "balance" might look like alternating between phases of intense work and deliberate rest, rather than trying to do both at the same time. Attempts to enforce constant equilibrium ("I must be perfectly composed and productive at all times") often backfire because they go against this law of oscillation.

It's more effective to allow the pendulum to swing: after a sprint, take a break; after extroverted socializing, allow some introverted downtime; after a period of structure and discipline, permit a bit of creative chaos, and vice versa. Oscillation is not only normal – it's necessary. As one trauma expert memorably put it, "the goal is to be like a flexible willow that bends with the breeze, rather than a brittle tree that snaps" when the wind blows.

Embracing Polarity as a Framework

Seeing polarity as a biological law elevates our understanding of human behavior from a simplistic "type" model to a dynamic framework. Rather than boxing people into static traits (introvert vs. extrovert, thinker vs. feeler), we can appreciate the ever-shifting interplay of opposite drives within each person. We're not one or the other; we are both, oscillating in response to needs, stressors, and energy reserves.

The myth is that balance means never teetering; the reality is that balance means continuous re-balancing.

For leaders, this insight is powerful: it encourages managing polarities rather than trying to eliminate them. For example, a team that's been in overdrive (sympathetic mode) might intentionally need a period of rest and reflection (parasympathetic mode) to restore its creativity and morale. An individual who has over-indexed on a strength to the point of burnout may need to swing back and nourish the neglected side (the classic case of the workaholic rediscovering family life or hobbies to regain sanity).

In summary, polarity underlies how our bodies maintain stability, how our behaviors manifest under stress, and how we allocate our finite energy. Embracing this concept moves us away from judging rigid traits or chasing static balance. Instead, we learn to ride the waves – recognizing when we've swung too far to one side and allowing the natural corrective swing to happen.

A system that moves is alive; a system that cannot move breaks. Polarity, in the end, is the law that keeps us adaptable, resilient, and whole – a biological framework for a fulfilling, dynamic life.